Things Change Quickly

Only a couple of months ago, the consensus view predicted a collapsing banking industry that would need to be nationalized. Banks were viewed as black holes with little chance of becoming profitable. Fortune Magazine was estimating future write downs of as much as $4 trillion. Citibank appeared to be on the verge of collapse. The Treasury hastily put together the Public Private Investment Plan (PPIP) to keep the banking industry solvent by purchasing toxic bank assets.

Then, virtually overnight, the situation seem to change. Today’s headlines are filled with stories of banks reporting record profits and attempting to return TARP money that they don’t want or need. Has every bank in the country suddenly become rock solid? Let’s examine some aspects of the banking industry’s “miraculous” turnaround.

Reported Profits Questioned

Wells Fargo’s Profits Look To Good To Be True –

April 16 (Bloomberg) — Wells Fargo & Co. stunned the world last week by proclaiming it had just finished its most profitable quarter ever. This will go down as the moment when lots of investors decided it was safe again to place blind faith in a big bank’s earnings.

What sent Wells shares soaring on April 9 was a three-page press release in which the San Francisco-based bank said it expected to report first-quarter net income of about $3 billion. Wells disclosed few details of what was in that figure. And by pushing the stock up 32 percent that day to $19.61, investors sent a clear message: They didn’t care.

Dig below the surface of Wells’s numbers, though, and there are reasons to be wary. Here are four gimmicks to look out for when the company releases its first-quarter results on April 22:

Gimmick No. 1: Cookie-jar reserves.

Wells’s earnings may have gotten a boost from an accounting maneuver, since banned, that it used last year as part of its $12.5 billion purchase of Wachovia Corp. Specifically, Wells carried over a $7.5 billion loan-loss allowance from Wachovia’s balance sheet onto its own books –

The upshot is that Wells could get by with reduced provisions until the $7.5 billion is used up, boosting net income.

Another quirk: The reserve was related to $352.2 billion of Wachovia loans for which Wells was not forecasting any future credit losses, according to Wells’s annual report.

Gimmick No. 2: Cooked capital.

The most closely watched measure of a bank’s capital these days is a bare-bones metric called tangible common equity.

Measured this way, Wells had $13.5 billion of tangible common equity as of Dec. 31, or 1.1 percent of tangible assets. Yet in a March 6 press release, Wells said its year-end tangible common equity was $36 billion. Wells didn’t say how it arrived at that figure. Nor could I figure out from the disclosures in Wells’s annual report how it got a number so high.

Gimmick No. 3: Otherworldly assets.

Look at Wells’s Dec. 31 balance sheet, and you’ll see a $109.8 billion line item called “other assets.” What’s in that number? For that breakdown, you need to go to a footnote in Wells’s financial statements. And here’s where it gets comical.

The footnote says the largest component was a $44.2 billion bucket that Wells labeled as “other.” Yes, that’s right: The biggest portion of “other assets” was “other.” And what did this include? The disclosure didn’t say. Neither would Bernard.

Talk about a black box. That $44.2 billion is more than Wells’s tangible common equity, even using the bank’s dodgy number. And we don’t have a clue what’s in there.

Gimmick No. 4: Buried losses.

How quickly investors forget. One week before Wells’s earnings news, the FASB caved to pressure by the banking industry and passed new rules that let companies ignore large, long-term losses on the debt securities they own when reporting net income.

Citi Swings to Profit, But Defaults Rack Units

Wall Street Journal –Citigroup Inc. said it earned a quarterly profit for the first time in 18 months, logging a $1.6 billion gain between January and March. But many of the banking company’s businesses continued to deteriorate.

Still, Citi’s bread-and-butter businesses, such as global retail banking and credit cards, suffered from swelling loan defaults.

The (profit) figures also include a $2.4 billion boost from a little-followed accounting adjustment under Financial Accounting Standards Board’s rule 159, which governs how banks value their debt.

Separately, analysts questioned whether Citi was skimping on its ongoing reserves, noting that borrowers defaulted or fell behind on loans at a faster clip than Citigroup socked away money to absorb coming losses.

Bank Bailouts Political Hot Potato

Certainly a lot of unusual items in the reported results, especially the $44 billion of Well’s “other assets” and Citi’s large gains from a questionable accounting change on mark to market. Since bailing out the banks is highly unpopular with the public, it is easy to conclude that the federal regulators gave the banks extreme latitude in accounting for certain transactions to make reported results look better than they would have. This accomplishes two things – it takes the bailout issue off the front burner and potentially builds public confidence that the banking industry is not on the edge of collapse. Whether or not this is just kicking the can down the road remains to be seen.

Liquidity Is Not The Problem

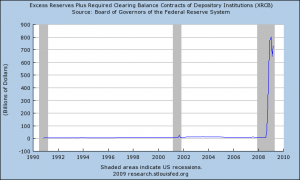

The Feds have literally been force feeding cash into the banking system to stimulate lending. Banks, having seen enough of the poor results of lending money that cannot be paid back, have concluded that lending more is not the answer. This can be seen in the massive increase in excess bank reserves that have piled up at the Fed.

Excess Reserves

Banks Have Learned Their Lesson On Dealing With The Government

It’s getting itchy under the TARP. Calling funds from the Treasury Department’s Troubled Asset Relief Program a “scarlet letter” for banks, JPMorgan Chase Chief Executive James Dimon said Thursday that his firm is eager to return the $25 billion they’ve received from the government, and will do so as soon as possible.

Many banks are eager to get out from under the government’s thumb. Earlier this week, Goldman Sachs ( GS – news – people ) announced plans to sell $5 billion in new shares to help repay its $10 billion in TARP funds sooner rather than later.

For Dimon, the goal seems to be steering clear entirely of the controversial government programs designed to rehabilitate the banking industry. JPMorgan won’t be participating at all in the Public Private Investment Plan, the Treasury’s program to buy unwanted assets from banks by matching capital from private investors and backing the assets with guarantees.

Dimon wants no part of it. JPMorgan will manage and sell its own assets, he says. “We don’t need” PPIP, he says. “We’re certainly not going to borrow from the federal government, because we’ve learned our lesson about that.”

Lesson For All

The cost of government aid far exceeds the benefits in the judgment of those running the banks. The bankers now seem more inclined to take their chances rather than tolerate the micro managing of their businesses by the Feds; certainly something to consider for any company contemplating a request for government “help”.

Whether the banking crisis is over is far from certain at this point. The economy remains weak and loan defaults continue to threaten the profitability of the banking industry. One thing for certain is that most banks do not want the heavy hand of the government destroying their franchise. Given the reality of these circumstances, the only banks likely to request TARP funds in the future will be the total basket cases. Forget the new “stress test” – going forward the Treasury can save time and taxpayer money by simply assuming that any bank weak enough to request aid should be closed down.