Massive Government Borrowing Raises Repayment Doubts

As governments worldwide attempt to sell massive amounts of debt, investors are beginning to question whether they are being properly compensated for default risk. The assumption that government debt is risk free is being re-evaluated as debt service payments increase to an untenable percentage of government revenues. Bond purchasers are further unnerved by the fact that there appears to be no end in sight to mounting government deficits as nearly every sector of the global economy demands loans and cash bailouts. Meanwhile, the collapse in corporate profits and massive job layoffs guarantees drastically lower government revenues at the same time that borrowing needs are escalating.

Recent events indicate that the capital markets may be unable or unwilling to fund unlimited government debt sales.

As countries compete for trillions of dollars of funding, markets are questioning long-held assumptions about the risk-free status of government bonds, and whether their ratings can weather the storm. Moody’s has waded into the debate by dividing its 18 triple-A countries into three categories.

At the top are 14 “resistant” triple-As, whose ratings aren’t being tested by the crisis, including Germany, France and Canada. The U.S. and the U.K. rank second as “resilient” triple-As. They face shocks to their economic model and very large contingent liabilities, but Moody’s thinks they can adjust.

Spain and Ireland, meanwhile, are “vulnerable,” based on their lack of ability to rebound. Ireland’s rating already has a negative outlook. Standard & Poor’s has downgraded Spain.

All of the sovereigns face mounting debt-to-GDP ratios, as debt issuance balloons and economic output declines.

Under Moody’s stress scenario, involving a further growth shock and permanently higher interest rates, interest payments for the U.S., U.K. and Ireland as a share of general government revenues would rise above 10% by the end of 2011 from 6.1%, 5.3% and 2.8%, respectively, at the end of 2007. Spain’s indicator would rise to over 5% from 3.9%.

The 10% barrier is crucial, as above this level debt service costs start to limit governments’ options. Double-A-rated Italy’s indicator was 10.7% at the end of 2007. Rome has admitted it can only respond in a limited way to the crisis because of its debt burden.

Japanese Bonds Fall With Rising Debt Sales

Feb. 16 (Bloomberg) — Japan’s 10-year bonds fell the most in a week on concern the government will spend more to revive an economy that shrank last quarter by the most since 1974.

Ten-year yields climbed from near a two-week low after the Cabinet Office said today the economy contracted at an annual 12.7 percent pace last quarter. Japan may expand its stimulus plans by 30 trillion yen ($323 billion)

Australian bonds also fell today as Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s government steps up debt sales to finance economic packages. Australia’s government is selling as much as A$24 billion ($15.6 billion) of bonds by June 30 as it increases spending to avoid the nation’s first recession in 17 years.

Korean Auction

The South Korean government’s auction today of 10-year bonds failed to attracted sufficient demand for a second consecutive month. The government raised 584 billion won ($409 million) at the sale today, less than the 800 billion won it was seeking.

Japan’s debt burden is the largest among G-7 nations relative to GDP, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Italy’s debt is equal to 117 percent of GDP, while the other five countries are below 70 percent, the data show.

Obama’s Promises Of Open Ended US Borrowing Deters Buyers

The Wall Street Journal notes that:

Prices of government bonds started to fall Friday, ahead of the vote by the House of Representatives that approved the $789.5 billion stimulus package. This decline could be the beginning of the capitulation the market has been bracing for since the administration of President Barack Obama took over, with promises of a recession-era boom in government spending.

No sooner had lawmakers reached a compromise on this spending program than yet another began to take shape, this time to help homeowners avoid default on their mortgages. Though the dimensions of this package are unclear — details are expected Wednesday — the bottom line is unequivocal. Each new rescue plan signals an expansion of government borrowing and more bonds flooding the market, which absorbed a record $67 billion last week.

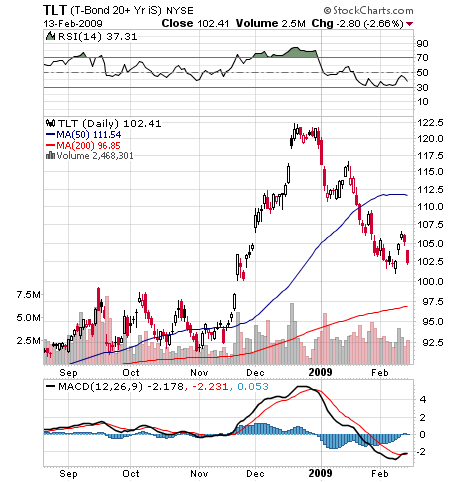

As we can see from the chart of the TLT, a proxy for the government long bond, the bond market has been selling off dramatically for weeks as the size of the stimulus package became clear. Major foreign buyers of our debt, such as China, are bluntly questioning our ability to repay. It is obvious to logical minds that there are constraints and consequences to a government’s determination to borrow money beyond its capacity to service the debt. South Korea and Germany have already had failed bond auctions, with insufficient investor demand to buy all the debt offered. Italy is so indebted already, it has given up trying to sell additional debt. Rational investors do not lend money to borrowers judged incapable of servicing and repaying debt.

US interest rates will continue to rise as Congress talks of further huge government borrowings. Higher borrowing costs will severely strain government budgets. The banking industry, corporate America and John Q Public all are demanding funding, bailouts and tax breaks. Congress’s promises to bailout everyone and to “spend us into prosperity” with borrowed money will lead to financial disaster. The out of control borrowing and spending will eventually result in the need for a bailout of the United States. At that point, the issue of default by the United States will no longer constitute an academic discussion – it will be real and the cost will be unimaginable. Hopefully, the ruling elite will not bring us to this final stage of national ruin.