Do Extended Benefits Reduce Job Seeker’s Motivation?

Excluding the depression of the 1930’s we are fast approaching a new official high in unemployment. During the depths of the last worst recession of 1981, unemployment exceeded 10% vs 9.4% today. If we include marginally attached and involuntarily part time workers in the unemployment numbers, the current unemployment rate exceeds 16%.

In response to the high level of unemployment and the difficulty of obtaining employment, Congress has enacted legislation that allows the unemployed in 24 states to collect up to 79 weeks of unemployment benefits. The other states allow unemployment benefits from 46 to 72 weeks. In more normal economic times, the limit on unemployment benefits was usually up to 26 weeks.

Washington legislators are now proposing another extension of benefits for up to another 13 weeks that would cost up to $70 billion. The additional extension of benefits was prompted by the fact that up to 1.5 million unemployed Americans would soon be losing their unemployment checks as they reach the current payment limits.

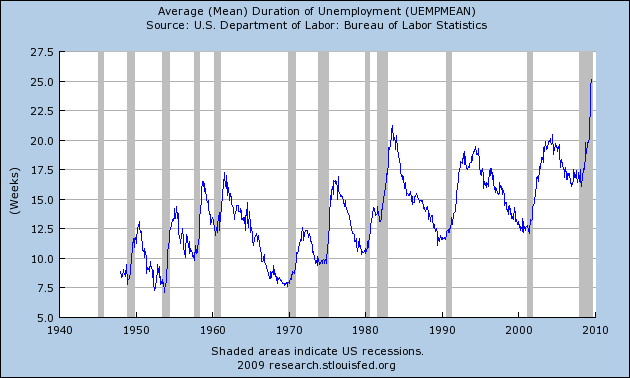

In addition, the duration of unemployment has reached new highs not seen since record keeping began.

Given the unprecedented level of unemployment, the duration of unemployment and well reasoned arguments on why unemployment will continue to increase, the entire concept of unemployment benefits should be reconsidered.

Should Unemployment Benefits Be “Free”? – Some Alternatives

- Is the constant extension of unemployment benefits reducing the motivation of the unemployed to seek new employment? In the past year I have tried to hire unemployed people for an entry level position in which the starting pay was comparable to or slightly above the level of unemployment benefits the job seeker was currently receiving. In almost every instance, the job seeker declined the job offer, preferring instead to postpone employment until benefits ran out. I have also heard this same story from other people. To maintain unemployment benefits, many states require that a benefit recipient contact a certain number of employers per week to seek work – how many of the unemployed merely go through the routine of seeking employment to maintain benefit payments?

- Should the economy weaken further and job losses continue, does it make sense for Congress to constantly extend costly unemployment benefits with zero obligation from the recipient? Bill Clinton reformed welfare by requiring benefit recipients to work. Why not do the same with the unemployed who are receiving benefits? Many charities, local governments, hospitals and companies could employ additional manpower in a variety of productive endeavors. The unemployment benefits would still be paid by the government, but the benefits would have to be earned. From a self worth perspective, getting engaged back into the real world would benefit the unemployed as well – sure beats watching television all day.

- Instead of spending hundreds of billions on unemployment benefits and getting nothing in return, the government could establish job training programs or put the unemployed to work on infrastructure projects that the country sorely needs. This was done in the 1930’s with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the country still benefits to this day from the roads, bridges, dams and buildings that were constructed. The preferred way to do this would be for government bureaucrats to get out of the way and contract projects to private industry. Paying people to do nothing accomplishes nothing.

Ideally, the economy recovers and private industry rehires many of the unemployed. Realistically, the country may face continued massive job losses or at best a slow recovery where the unemployment rate remains in the 10% plus range for an extended period of time. Maintaining an army of paid and unemployed workers to sit idle makes no sense.

When The Laid-Off Are Better Off

Would it surprise you to learn that survivors can suffer just as much, if not more, than colleagues who get laid off? “How much better off the laid-off were was stunning and shocking to us,” says Sarah Moore, a University of Puget Sound industrial psychology professor who is one of the book’s four authors. “So much of the literature talks about how dreadful unemployment is.”